“No person will make a great business who wants to do it all himself or get all the credit.”

Andrew Carnagie

Delegation is a key skill every leader must master in order to be fully effective. From my observations it’s a skill that takes years to develop beyond being a simple means of shifting tasks from oneself to another. I’d offer that truly effective delegation – the kind that results in growth in employees and achievement of organizational goals – is an art.

Through delegating, you open up your time for investment on the most important tasks for which your strengths, or position, are best aligned. It’s not about getting rid of work you don’t want to do. It’s about leveraging other people’s skills and energy to open up your time to accomplish more of the right things for your organization and your clients.

The skill of delegation becomes vitally important, as you progress forward from employee responsibility for just your tasks, to manager responsible for your tasks, the tasks of others and organizational goals. Without a process for delegating and an appreciation of both your comfort with delegating and the abilities of your people, you will quickly find yourself unable to keep up with increasing work loads, client demands, and mission requirements. This in turn, will lead you to disenfranchise your direct reports and hamper your future promotability.

If you’ve had the chance to observe a leader who is successful and effective in delegation, you’ll begin to see that how they do it, follows a process. There are a number of actions that they consciously consider before making a transfer of task and responsibility to an employee. Through this process, they develop confidence in themselves because they are following a framework versus simply handing off work and hoping it turns out to their expectation.

“If both you and your employees are doing the same work, it’s redundant. It’s also a major waste of resources.”

On the other hand, the leader who is less effective at delegation doesn’t have a framework for assessing transfer of task. The result is that they never develop confidence in themselves or their people and ultimately end up as a micromanager or worse: a work-hoarder, never willing to pass along work to others for fear of failure or sub-par results.

Each of us, even the micromanagers among us, know that micromanaging isn’t good for anyone and sub-optimizes organizational effectiveness. When you micromanage you siphon away mental energy from the work that only you can accomplish, because you’re spending your time doing your employees work a second time. You also do your employees a disservice by not allowing them to grow into responsibility and develop their own technical and non-technical skills. If both you and your employees are doing the same work, it’s redundant. It’s also a major waste of resources.

How can you be a technically proficient leader without micromanaging?

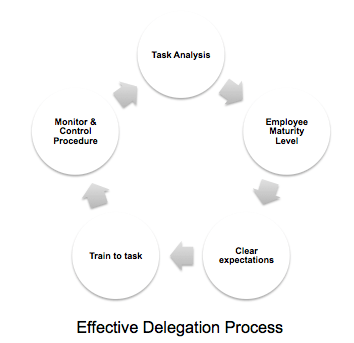

Delegation must never be left to chance. There is a five step process you follow to build your confidence that the work you delegate will be accomplished to expectation and deliver intended benefits to the organization. As you learn how to employ each step in your own way, each will become second nature and you will begin to master the art of delegation.

1. Conduct a task analysis. Before you can delegate anything you need to know what the universe of tasks is under your purview. What are you responsible for? What does the task entail? Is it highly technical or routine? What is the impact to the organization/client if it fails?

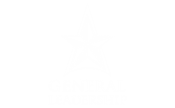

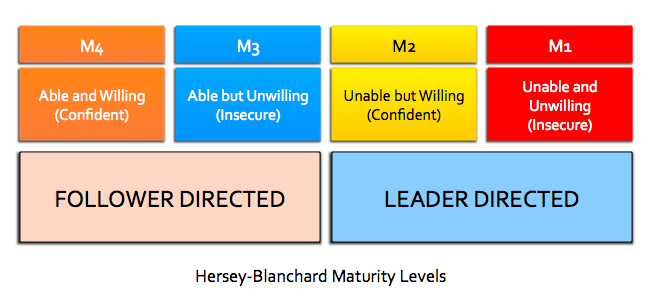

2. Understand your team’s strengths and weaknesses. Next, evaluate the maturity and skill levels of your employees. The Hersey-Blanchard Situational Leadership model is useful here, as it helps to frame leadership style with maturity level of one’s employees. Based on this model, knowing when to employ certain leadership styles depends greatly on the maturity of the employee. They break maturity down into four different levels:

M1 – People at this level of maturity are at the bottom level of the scale. They lack the knowledge, skills or confidence to work on their own and often need to be pushed to take the task on.

M2 – At this level, followers might be willing to work on the task, but they still don’t have the skills to complete it successfully.

M3 – Here, followers are ready and willing to help with the task. They have more skills than the M2 group, but still not confident in their abilities.

M4 – These followers are able to work on their own. They have high confidence, strong skills and they’re committed to the task.

To make all of this simple to digest, the Hersey-Blanchard model can be viewed as a matchup between leadership style and maturity level.

3. Set clear expectations. Without clear expectations, both you and the employee do not have an established framework against which to gauge work performance, delivery of benefits, or a clear understanding of what constitutes “task accomplishment”. Setting clear expectations can oftentimes be articulated best through use of a RACI Matrix (which stands for Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, Informed) to clarify tasks. This is a classic project management tool used to ensure a project team is clear on who’s doing what, when, how and with whom.

4. Train your people to the task. If you accomplished an assessment of your team’s capabilities, then you may uncover employees lacking requisite skills for all of the tasks you’d like to delegate. These are opportunities, where feasible, for enhancement. As a leader you must design a way to train them to accomplish the tasks at hand. This holds especially true, in situations where you must free up time to allow yourself to accomplish the work you, and you alone, can do.

Depending on the complexity of the task, you may have to send the employee off for specialized training. In other situations, you may be able to train them yourself through a standard operating procedure checklist and training session. Instead of a burden, view this as an opportunity to enhance the skills of an employee and for creating margin in your schedule to accomplish your work with greater impact. When the training is done correctly, you not only build capability in your employee, you build self confidence in yourself that the work will be accomplished to your liking.

5. Trust but verify. Ronald Reagan got it right from the perspective of effective delegation when he quipped “trust but verify”. Whenever delegation takes place, as a leader you must have a means for monitoring and controlling the task accomplishment. This doesn’t mean you need to micromanage (again, an indication of your lack of confidence, poor task transfer procedures, training, or misinterpretation of the employees maturity level). It does mean that you follow-up on the work being accomplished by your employees. In project management, one of the main domains is monitoring and controlling. It isn’t meant to stifle operations or creativity – it’s meant to ensure that tasks are being accomplished according to plan, schedule, and within resource constraints.

Whenever delegation takes place, as a leader you must have a means for monitoring and controlling the task accomplishment.

Throughout my career I’ve told my employees to expect me to trust but verify their performance. Although I’ve delegated a task, I still reserve the right (a.k.a. responsibility) to performance and task accomplishment. As a leader, so should you. Delegation doesn’t equal abdication, so it’s important that your employees know that, although they have responsibility for the tasks you’ve assigned, they can expect you to periodically check in on performance. The best way to do this is through routine, scheduled progress reviews or milestone checks.

It’s critical that you avoid leaving delegation to chance. By following this process, you reduce risk of organizational, employee and your failure, while greatly increasing the likelihood of success. At the same time, you are increasing your employees capacity for responsibility, skills, job satisfaction and engagement.

Reference:

Hersey, Paul. Situational Leadership Some Aspects of Its Influence on Organizational Development. N.p.: n.p., 1975. Print.