“Luck is of little moment to the great general, for it is under the control of his intellect and his judgment.”

“Luck is of little moment to the great general, for it is under the control of his intellect and his judgment.”

Titus Livins

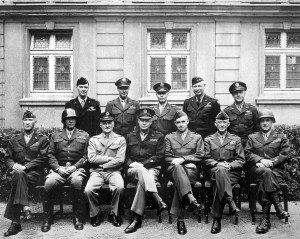

The Allies just lost over 10,000 service members at the Chosin Reservoir in late 1950 and retreated back to the original positions they held before the battles began. The blame for such tragic losses was attributed to poor leadership—more specifically, at the generals in charge. To put it bluntly, there was a lack of generalship.

On the heels of this devastating defeat our nation’s most senior leaders knew they needed to make a change. Enter General Matthew Ridgway.

Ridgeway was assigned the position of Commander, Ground Forces in Korea and in a relatively short period of time, the morale and attitudes of his men dramatically turned around. With their new-found confidence, the same forces that had been decisively defeated a short time earlier were able to turn the tide and salvage the Korean War. What was the difference that GEN Ridgway brought to his command? Superior GENERALSHIP.

Generalship Defined

Generalship is defined as “military skill in a high commander.” Military leaders are trained in leadership at the earliest stages of their careers. Officers learn officership as they progress through the ranks and experience the rigors of leading other dedicated, talented men and women. But one learns generalship not in a classroom, but through observing and experiencing other senior military leaders who themselves effectively exercise their generalship in challenging situations. Said another way, Generalship, like leadership, reflects a learned set of skills that equip us to effectively move things forward in our spheres of influence.

Traits of Generalship

As can be seen, each of the traits of Generalship can and should be readily adopted by those in positions of leadership in every sector—government, private sector, nonprofit organizations, and yes, particularly the military. Here are the top 10 traits of Generalship that describe what every leader must be:

STRATEGIC VISIONARY – Think, act, lead and develop others in a strategic manner. Be out in front of the fray. To an extent, you have to be a futurist or be able to look at things and see the art of the possible. Generals have to take risks to have a shot at success and ultimately win wars. The key here is to be willing to move out in uncharted territory.

DECISIVE – Make decisions and make them at the right time. Exercise prudence to insure snap judgments or delayed decision-making doesn’t hinder achieving critical mission objectives.

COURAGEOUS – Exercise physical and moral courage to serve as the beacon for others to emulate and follow. Moreover, leaders do the right thing for the right reason at the right time.

ACCOUNTABLE – Lavish praise on subordinates when victories occur and take responsibility when the team falls short of their objectives. Always start corrective actions with ones’ self.

INTEGRITY – This is flat out non-negotiable! There is no room for questionable character in Generals, generalship or leadership.

DRIVE – Make something happen. You can have a good plan and a good team but someone must drive the team to the top of the summit.

TEAM BUILDER – the team that must be built here is very high level. Coalitions and disparate parts must be brought together in unison to achieve much higher goals.

CHANGE AGENT – Recognize who or what needs to be changed and then commit to making the required changes. Most people focus on the what, forgetting that the WHOs are the ones that drive the WHATs.

STANDARDS – Maintain high personal standards for oneself. Equally important is to set and enforce the standards for the rest of the organization.

POISE – Lead with flair and class and always conduct yourself in an unflappable manner.

DIPLOMATIC – Create political alliances outside of your own organization to achieve common goals and objectives.

Generalship In Action

History books and recent media coverage provide numerous examples of senior military leaders regularly demonstrating these traits of effective Generalship. But unfortunately, examples also abound of leaders who have gone astray. Both provide learning opportunities for aspiring leaders to evaluate their leadership style and to make the choice to espouse the traits of Generalship. For just as General Ridgway’s predecessors displayed poor leadership and as a result, lost a large number of lives; Ridgway used many of the traits of Generalship to transform his command and successfully execute his mission at a critical point in history. This is testimony to how leadership doesn’t just make a difference, it is THE difference that distinguishes between experiencing subpar outcomes and achieving extraordinary results.

Now, more than ever, our country, government, organizations and communities need leaders who espouse the traits of Generalship. What traits do you need to work on to develop your own form of Generalship?

This post topic reminds me of Edgar Puryear’s “American Generalship: Character is Everything: The Art of Command.” Excellent read and a good complement to the traits listed here.

A key element required for all of these traits is what Joseph Grenny, et al in “Influencer: Leading the New Science of Change” calls deliberate practice. That is to say, we must give our leaders at all levels deliberate, specific practice in developing and honing these traits over time. We must allow for mistakes and failures along the way, otherwise people will not likely attempt the behaviors needed to establish these traits in the first place.

If done well, we end up with a story I heard regarding a journalist covering a General Officer’s staff meeting early in the 2003 Iraq War. The staff was throwing rapid fire questions at the General left and right. Almost without pausing, the General answered each question in quick succession. As the meeting concluded, the journalist approached the General and asked, “Sir, how was it possible for you to make those decisions so quickly and confidently?” The General replied, “I didn’t answer those questions quickly. It took me 30 years.”

When the best leader’s work is done the people say, ‘We did it ourselves

The reason why I missed promotion to Admiral was because I was short in nine of the required eleven attributes.

Looking forward to learning from great leaders.

I need copies of your leadership writings to help shape my reasoning in order to cope with the 21st century dynamics of leading.